Forced IUD contraception faces criticism in China

by Lin Meilian

A woman’s body does not really belong to herself. It can belong to the State in some cases. Deng Yanqin, mother of a newborn son in Jiangxi Province, discovered this when she was told by the local residential community’s administrator that she would not get a hukou, or household registration, for her firstborn unless she placed an intrauterine device (IUD), a contraception ring, inside her womb.

“How could they do this to me?” Deng asked, “And more importantly, do they have the right to do this?”

This question has been asked by thousands of couples all over the country who encounter the same problem. The answer, according to a group of 13 lawyers who called on China’s top family planning authority to abolish forced IUD implants earlier in December, is “No”.

“There is no law that forces Chinese women to undergo contraception surgery when applying for her firstborn’s hukou,” Zhang Lijuan, one of the appeal’s initiators, told the Global Times.

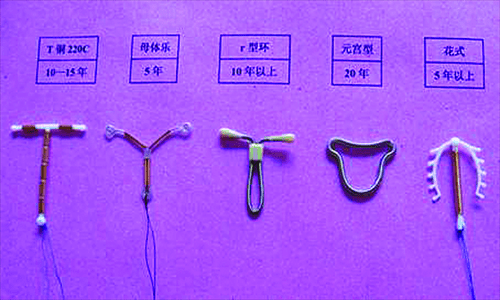

The IUD is one of the most widely used forms of birth control in China, especially in rural areas. According to the Ministry of Health, 7.8 million women underwent IUD surgery in 2009.

Forced IUD implants, which were widely used in the 1980s to prevent women from having a second child, have been relaxed in recent years. Now, women living in big cities such as Beijing and Shanghai can make their own decisions about birth control. However, it has since been linked with other measures such as applying for hukou registration or land to build property.

Deng and her husband wrote to the local family planning authority asking for an explanation. They were told it was because “they have not proved they were using any long-term effective contraception measure”, so the authority could not issue them the documents they need.

“Women have the right to choose what kind of contraception they want,” Zhang said. “As a female lawyer, I feel like I need to stand up and fight for them.”

In September last year, three months after her baby girl was born, Li got a call from the local family planning authority at her village in Hubei Province asking her to come for a physical check. Thinking it was a routine examination, she went along. They then took her to a clinic to see if she was able to undergo IUD surgery.

“I told the doctor again and again that I know about birth control measures, and they can’t force me to do it,” she said. But the family planning official told her if she refused, they would not assist her in obtaining documents she would need in the future.

“It sounded like a threat, so I had no choice but to do it,” she recalls.

Women’s freedom to choose contraception does not seem to matter when it comes to the family planning policy. The policy, which was applied in 1979, restricts urban couples to having one child, while allowing rural couples, ethnic minorities and couples who are both only children themselves to have additional children. It is estimated that the policy has prevented over 400 million births from 1979 to 2011.

However, the policy is controversial both within and outside China, as cases of forced abortion and sterilization have been repeatedly reported by the media. Earlier in June, a widely circulated photo of a woman lying next to her baby’s corpse sparked outrage on the Internet. Feng Jiamei from Shaanxi Province was reportedly forced to have an abortion in the seventh month of pregnancy because she could not pay the fine for having a second child.

The 2009 novel Frog, by this year’s winner of the Nobel Prize for literature, Mo Yan, chronicles the lingering pain that has haunted many Chinese women for three decades.

In the novel, Frog’s aunt helped deliver 10,000 children before the implementation of the family planning policy in his village. After the policy was adopted, Frog saw his aunt become haunted by the forced abortions she witnessed.

“The family planning policy is a basic condition of China dealing with the most conservative element of traditional culture. It touches the sorest points and most delicate parts of the souls of millions of Chinese people,” Mo was quoted by Sina.com as saying.

Xie Juan, 30 and mother of a 1-year-old daughter from Guangdong Province, managed to avoid the IUD surgery.

“I managed to get a doctor’s note to prove my health condition was not suitable for the surgery,” she told the Global Times. “But I am afraid they will force me to do it through other methods.”

Back in the 1970s when the policy was adopted, male sterilization was encouraged. When a man had the operation, villagers would march to his place, beating gongs and drums to celebrate his “contribution” and provide him with rich food.

Now it is the women who take the risk, often because they do not want their breadwinner husbands to risk getting infections or complications.

Compared to Chinese women’s unwillingness to place a contraception ring inside their wombs, studies have shown that more American women are choosing IUDs for birth control.

In 2009, 8.5 percent of American women using birth control chose an IUD or implant, with the large majority going with the IUD, 4 percent higher than in 2007, according to the journal Fertility & Sterility.

With the devices, it’s estimated that between 0.2 percent and 0.8 percent of women will have an unplanned pregnancy within a year. By contrast, with contraceptive pills and condoms, the unintended pregnancy rate is about 9 percent per year, it said.

Some unmarried women even bring it up in conversation with doctors, but get rejected because “they are not in a relationship.”

Even though IUDs are believed to be one of the most effective forms of reversible birth control, it is still far from popular in the US and way behind birth control pills and condoms.

There are also concerns that some poorly designed devices might result in infections or even death.

American women’s concerns seem well-founded. One month after being forced to undergo IUD surgery, Li found that there was something wrong. She went to see the doctor and was told she had a vaginal yeast infection.

The doctor insisted it had nothing to do with the IUD surgery and that she could be cured. After 10 months of fruitless treatment, she decided to examine the device. But another problem emerged. To do this, she needed official permission from the family planning authority.

She went through a number of procedures to get the letter and had her device checked. It turned out there were indeed problems. The device had been poorly installed and had now become stuck to her body.

But to remove it, she needed another permission letter. She scrambled around and collected the documents she needed. Later, the doctor told her she had to wait until the vaginal yeast infection had gone. Another letter was required to get the medicine.

“I remember I stood there and started crying like a baby. I felt sorry being a woman in China,” she said.

Kong Xingxing, a former researcher at Nanjing University and now a family planning authority official in Shandong Province, calls these women the “silent group.” There is no official number of how many women are facing complications from contraception surgery, because most of them don’t talk about it.

“We can’t just focus on the glorious achievements of the past three decades and ignore their consequences,” she told the Global Times.

“These rural women in their 50s are the victims of State policy. They are scattered around different villages and don’t know how to protect their rights,” she added.

Through her research and interviews with rural women, Kong found that the majority of them chose to deal with the problem by themselves.

“Most of them would buy painkillers rather than see the doctor or tell their family,” she said. “Crying is the only way to let out bad feelings.”

Some are afraid of taking the IUD out themselves, as in some places, family planning officials will check the ring. If they find it has gone, the women face a fine, Kong said.

The medical malpractice committee under the family planning authority determines whether a woman faces complications from contraception surgery. If approved, the woman receives compensation. But Kong questions its credibility.

“It is just like asking a murderer to admit he or she is guilty,” Kong said.

Some people, like Zheng Zhiyuan from Zhejiang Province, cannot sit back and watch his wife suffer. He said his 36-year-old wife felt sick right after she had the sterilization surgery after giving birth to their second child in 2008.

“She couldn’t even stand still after the surgery. I had no idea what was wrong so I asked the doctor. He just told her to rest at home,” Zheng told the Global Times.

A year later, she was diagnosed with amyotrophic lateral sclerosis in Beijing, a debilitating disease characterized by rapidly progressing weakness and muscle atrophy. She has difficulty speaking, swallowing and walking.

There is no evidence to prove that this is a result of complications from contraception surgery, but Zheng believes that the poorly conducted surgery was the cause. He petitioned the local family planning authority in 2009 but was beaten up by security guards. He contacted the medical malpractice committee asking for compensation, but was rejected.

Over the years, eye contact has become their only method of communication. Every time he goes home, he looks in her eyes and tells her, “I will never give up on you.”

Source: https://www.globaltimes.cn/content/753485.shtml